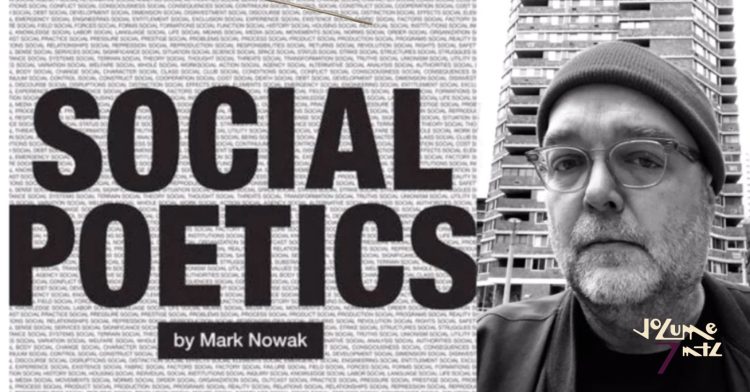

Volume 7 MTL: Worker Poetry with Michael Nardone and Mark Nowak

Remarkable poet Mark Nowak and Montreal-based poet and editor Michael Nardone discuss the contours of Nowak’s singular literary production over these last two decades. The conversation will focus on Nowak’s ongoing body of worker poetry – represented in his groundbreaking books such as Shut Up Shut Down and Coal Mountain Elementary – to open up a dialogue on Nowak’s most recent essay, Social Poetics. This work documents the imaginative militancy and emergent solidarities of a new, insurgent working class poetry community rising up across the globe.

The following is an edited transcript of a conversation between Michael Nardone and Mark Nowak as part of the Volume 7 MTL art book fair and conference, on October 5, 2024 in Montreal.

Michael Nardone: Mark has published this important book, Social Poetics, that I regard as a summation of perspectives that have been present in your work over the past couple of decades at least. In it, to define a social poetics, he draws on the work of Langston Hughes, Amiri Baraka, and the Kenyan writer, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, amongst others. In beginning our conversation, I thought I might ask Mark describe this genealogy and also what he means in articulating a social poetics.

Mark Nowak: Sure. So, for a long time I was teaching, in addition to teaching at [a] college, poetry in schools and poetry in the prisons. And I had been doing that since the late eighties.

But you know, I came from this really working-class background. Everybody in my family worked in a factory. And I kind of wondered, somewhere along the line, if I could take this model of teaching poetry in schools, teaching poetry in the prisons, and take it into factories, workplaces, union halls, etc. I did it first in Chicago with a group of Teamsters, plumbers, [and] others.

But the first bigger project was: I lived in the Twin Cities in St. Paul, Minneapolis, and there was a big Ford assembly plant that announced that it was closing. And I had a close relationship with the UAW, the Auto Workers Union there, so I said to them, “What if I taught a poetry workshop between shifts?” And surprisingly, they said yes. So we put a little announcement in the UAW newsletter. Some people signed up and in between shifts they came and they wrote about this experience of having worked in this factory for 30 years, 40 years, uh, a lifetime; some of them having kids who had just started there. And it was this incredible poetry that came out of it.

And when that happened, I got a small travel grant from a local foundation to go to South Africa because my own poetry book, Shut Up Shut Down, had come out from a press in the Twin Cities, Coffeehouse Press. When I found out that I was going to South Africa, I wrote the union there […] because I knew there were Ford plants.

And in the great kind of tradition of South Africa, where the idea of doing literature and union organizing had always been together, they wrote me back. It was funny because, you know, I’ve been trying to get other workshops like this in the States forever; no one ever answered the phone or answered my email. And South Africa, they wrote back a two-page letter with: “We’d like to have you come these two days in Port Elizabeth, these two days in Pretoria. Here is the schedule. Here is the mobile number for your driver who will pick you up at the hotel. Are you a vegetarian for the catered lunch?”

So, this whole project kind of grew out of just sending an email. And I wanted to write Social Poetics in a way that wasn’t a series of essays that would feel really distant to the participants in the book.

A lot of the book is about a group I’ve run for 15 years now called the Worker Writers School. And in New York City, we collaborate with and have writers from different worker centres. So a lot of Caribbean and Central American nannies, care workers, elder care workers, the New York Taxi Workers Alliance members, the Street Vendor Project, which has members who sell at the falafel carts on the streets and things like that.

And we get together once a month, and we write poems. And we publish them in chapbooks and books, and more recently, light projections and neon signs, and have been doing that now for 15 years.

Michael Nardone: Do you teach workshops in university settings as well?

Mark Nowak: Yeah.

Michael Nardone: I went to graduate school for writing, having never been in a creative writing workshop before. And the program I went to was quite conservative, and the workshop model practiced there reproduced a certain approach to poetry over and over again that I felt was quite limited in terms of what poetry and poetics can be. Because of this, I’ve never been too interested in that model for teaching poetry, but I’m impressed by how you outline a different possibility for it. So, I’m curious if you might discuss your approach to the form of the workshop, as you devote an entire chapter of the book to a discussion of it.

Mark Nowak: Yeah, you know, part of me really loves the workshop model, right? But I grew out of initially teaching for a long time at a community college for 15 years which was open enrolment. You know, there’s a lot of immigrant, refugee students. The workshops at the Worker Writers School are not that different from that. To be able to have an opportunity to write a haiku about their job at like Costco or the restaurant server or working in the gas station, like no one ever asked them to do that, you know? No one ever said, “This is something that you can write about.”

When I started the workshops, it was because I had seen in Buffalo where I grew up factory after factory close. Literally all the factories of everybody on the street where I lived and people didn’t have any way to express anything about that other than drinking themselves to death or whatever the case may be, right?

I wanted a space for people to say, “This was my job. I did it for 30 or 40 years. I loved my co-workers, but my daughter works here and she just got a mortgage on her house. And where else is she going to earn 50,000, 60,000 a year?” You’re not going to do that working at McDonald’s after the Ford plant closes. Like, you’re in grief and despair. So having a place to do that became really important, you know?

My wife videotaped the workers outside the Ford plant reading their poems in Minnesota. And then I took that DVD and took it to South Africa and showed the video in the plants in Pretoria and Port Elizabeth. And those workers wrote poems back. And their discovery was, they thought the American workers lived on gold paved streets, right? And their jobs were perfect. And the workers in the U.S. thought, “Oh, the South African worker is stealing my job,” right? And both learned a really important lesson from poems just going back and forth. Because you never have a chance as a worker in either of those countries to even so much as to meet a worker in one of the other countries.

And in fact, when I got to Pretoria, we couldn’t do the workshop at the Ford plant. The management had banned any visitors for the week I was in the country from coming there […] because they were worried about that happening! About workers from one country in another country talking to each other, you know? Who knew poetry could be so dangerous?

Michael Nardone: Two things come up here. With that sense of solidarity not only is the foreclosure of people’s lives and livelihoods in this, like, financial world that we live in right now, but there’s also a foreclosure of spaces of communication and expression. One of the ways to prevent, you know, the despair and the encroachment of fascism – that feels all too real right now – is to actually create spaces where people can actually express what they’re experiencing.

Mark Nowak: Yeah, I mean, you know, it was interesting to try to trace a history in the more accepted somewhat literary world to then connect to the work we do at the Worker Writer School, right? And so, one of the things that happens in the book is that it starts out with Baraka, who was a mentor of mine, […] and his kind of persistent ability to move inside and outside of those academic spaces, you know? Like I once hung out with Baraka at the Communist Party, USA National Convention. And he was seen as a poet, but also a philosopher and a political leader, right? And so that tradition then allowed me to connect internationally with a kind of worker writing tradition.

In Nicaragua, in South Africa in particular, where unions held creative writing workshops, published books of poetry – one, Black Mamba Rising, I talk about quite a bit – had events at soccer stadiums where poets read; [they] had crowds like that. It was an unbelievable tradition.

Michael Nardone: [Addressing the audience] Mark does a kind of reading engagement with a series of Foxconn workers that I find fascinating because these are the people who are building our iPads, our iPhones, every kind of digital contraption, in this mega factory that must be more vast than I could ever imagine.

The factory suffers from a massive suicide rate, to the point that the CEO set up this kind of cynical net, uh, to catch the workers from the factory building. And the poems very subversively document the existence of these workers.

And there’s something fascinating about the poet figure. There’s something about, in my mind, worker poetry that one is one among many? And so the author function happens in a very different way. Yet one is one within many. And so, I’d be curious to hear something more about the figure of the worker poet as a kind of form or something like that.

Mark Nowak: You know, I think one of the great things about being here at the book fair is that a lot of this work comes out through, you know, people like Josh MacPhee designing this chapbook for us, right? The worker poetry tradition isn’t something that appears in the glossy New York publishing houses or in, you know, the big magazines. It’s from spaces like this. How can we get that work out there, you know?

One of the things we’ve really been experimenting with a lot in the last couple of years is the idea of light itself as a publishing mechanism. We’ve collaborated twice with the Dia Art Foundation, which has a long tradition of working with visual artists who have worked with language and light. And then last year, on May Day, we worked with them and a projectionist called The Illuminator in New York City […] to take a whole group of worker poems and project them on the stanchions of the Brooklyn Bridge.

I just remember really clearly one of the poets in the book, Davidson Garrett. He had been a yellow cab driver for 40 years. He said, “I can’t even tell you how many hundreds of times I’ve driven passengers over the Brooklyn Bridge. And there are my words on the bridge for everybody to read and see for one night.”

And so, we’re looking at ways to try to use different types of publishing mechanisms to get that work out, because we know it’s not going to appear in The Atlantic magazine.

Michael Nardone: That’s great. I mean, there’s something fascinating here because it’s like a transformation of the poet figure, but also the reading audience.

Can you talk about, in undertaking these workshops, [any] things that have surprised you?

Mark Nowak: I think one thing that surprised me is the often disinterest from the larger literary community. Like they’re interested in the idea of the workshop, but they’re not interested in the product of the workshop, right? I think another thing is the longevity – like, I never imagined that when we started these in New York City in 2010 or 2011, that now, through the pandemic and everything, there would be people who were in those very first workshops who are still coming.

Like people always say in the U. S., every six months, there’s a column in one of the big newspapers or something: “Does Poetry Matter Anymore?” And like, here’s someone who’s a taxi driver or a care worker or elder care worker who’s been taking a poetry workshop for 14 years.

I mean, they should have read everyone, right? Because we use Baraka and June Jordan, Darwish, Cuban poets, Chinese worker poets, you know, Shakespeare – we use everything, right? They should basically have a MFA in creative writing at this point, but they’re not given any footing in the literary world.

I think a lot about distributing this work. And in certain ways, because of social media, it feels a little bit easier. But that’s such an ephemeral distribution platform. You know, I’m sure we could have a great conversation with people at every single table here today about “How do we get this work out to more people,” right? And I don’t know, we should probably have set this table up on the corner outside and had this conversation because people would stop.

And I could hand out copies of this anthology or some chapbooks, you know, sell them for $5. “Look! These are all workers writing poems!” It’s like this perpetual challenge of all this work we do, is how do we get it out to people who would be interested.

But I remember watching this film about Bertolt Brecht and in it, Brecht said that on his tombstone, he wanted written, “He made suggestions.” And I just love that idea. Like, let’s turn a poem into a neon sign in a front window. Let’s project it on the Brooklyn Bridge. Let’s hand it out on the corner and do, you know, workshops. Like, what are other models that we can use to get this work out there?