Volume 7 MTL: Filling Gaps – Self (Trans)lation x Speculative Typography with Le Lin

Filling Gaps is a speculative typeface that consists of reimagined Chinese ideograms which all have diverse visual forms, unique sounds, and tell a story of their creation. As a trans Teochew artist / activist / designer, Le Lin explores different ways in which typography can illustrate certain aspects of our lives, either through unlearning or relearning it. What are the origin stories of the words we use daily? How does language govern the way we perceive ourselves? Who has the right to reimagine our futures?

Le Lin is a trans Teochew-Canadian multi-disciplinary artist, activist, and researcher based in Tiohtià:ke, Montréal. Most of their recent works have been silk-screen or risograph-printed artist books, always pushing the boundaries of traditional books. Le Lin is a firm believer in mobilizing art as a tool of resistance, instigating acts of vulnerability, and channels to uplift one another.

The following is an edited transcript of a presentation given by Le Lin as part of the Volume 7 MTL art book fair and conference, on October 5, 2024 in Montreal.

Le Lin: Hello! Bonjour. My name is Le. My full name is Le Lin. @spicybaby.jpg. And my origins, I’m from Chaozhou, from China. I grew up in Canada since I was six, and I moved to Montreal for university. I went to Concordia for printmaking and design. And for the past four years, I was in Japan. I was teaching English, I was living in Tokyo, and I worked for a risograph printing studio (Hand Saw Press).

Currently, I moved back because my visa expired. So, right now, I’m focusing on printmaking in Atelier Circulaire. And much of my projects and focus is based on Chinese design, and my interaction and relationship of being trans and queer with design and typography in Chinese.

First, I want to ask you a question. And after I ask you a question, I want to talk about my relationship to type design and typefaces and my relationship to language and how does language and design interact with each other? I believe most of us speak more than two languages. So how do you see yourself expressing in each language? And how do you make space for yourself in each language? So that’s my first question for you. And my second question is, as a designer or an artist, how do you express your identity through your art or design?

Both are similar. But I think, as an artist trying to blend those two together, it’s kind of a challenge sometimes.

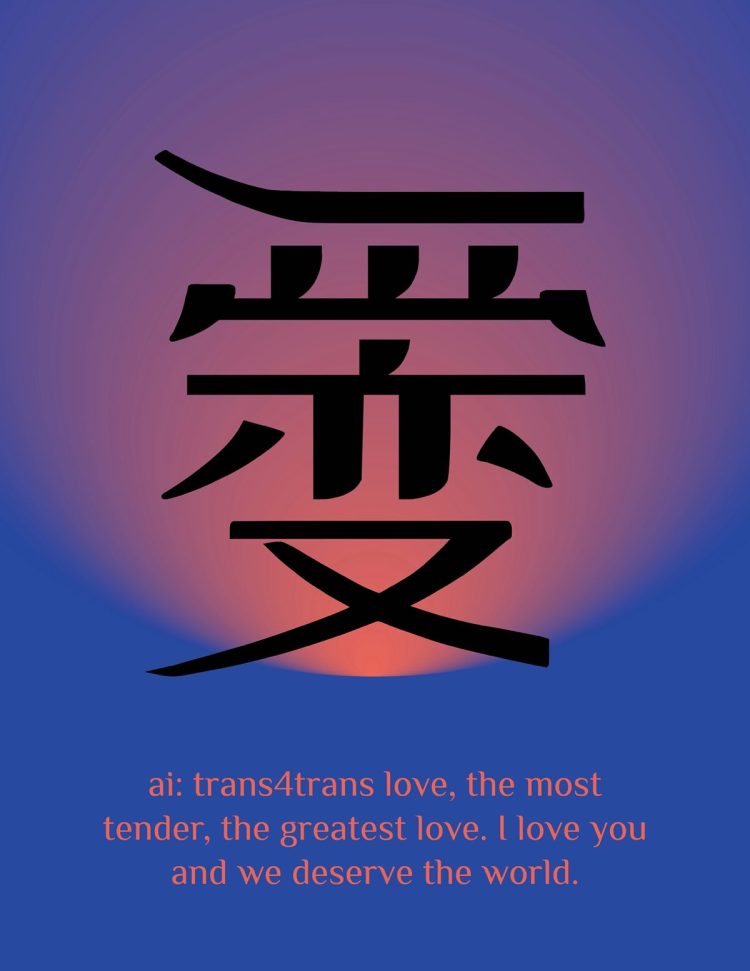

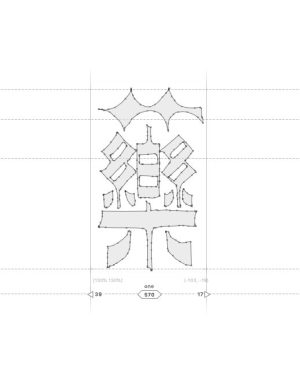

This project is a typeface where I created new Chinese characters by blending other parts of different characters that I resonate with. Some of them are actually existing characters, but no one uses them anymore.

I’ll just give an example. This one is, if you know the top, it’s the top for 爱, “love.” And the bottom part is 变, “change.” It’s kind of like the tenderness I feel for trans love, and how there’s not much representation in expressing my trans identity in Chinese. So, I wanted to create this character to resonate with trans-for-trans love. And of course, being trans is not one-directional, it’s a thousand directions. […]

I’ll just do like, one more example. Two more. So, this character is the character for “home,” or 家, as the top hat. And basically, being part of the diaspora, I don’t recognize myself having a home that is grounded. I decided to put my body inside my home. It represents carrying my body as a home wherever I go. And it’s different, especially being in a queer body, to feel at home, being displaced. This is something I created to make me feel more at home.

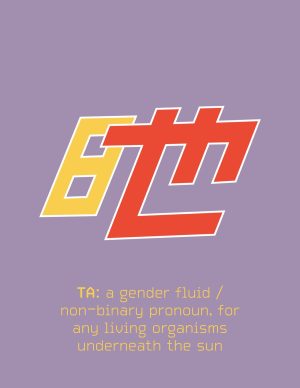

This character, the pronoun for 他 in Chinese is with the ‘human radical’. The human has two legs. But because in the 19th century – 1870 to be exact – because of the westernization of feminism, the woman radical was introduced to China. And in traditional Chinese texts, you don’t recognize the gender of the person you’re talking about. But because of the introduction of “oh we need to talk about women using the female radical,” it was introduced later.

It’s interesting because… I didn’t want to talk about the character in a way that’s about the past. I wanted to bring something of us in the future. So, the radical here 日is for 太阳, the sun. Because we all live under the sun. So, it’s kind of like, how do I identify myself in the future using Chinese?

In French and English and Latin-based languages, we often wear a pronoun like a badge. Our identity is always in the front of how we present ourselves. But in Asian languages, like Chinese or Japanese or Korean, we often don’t express that in our language at all. And our queerness or our transness or different parts of our identity are always hidden behind the language. So, it’s like, which one do you prefer? Do you prefer to wear it like a badge? (I mean, you don’t have to prefer.)

It’s interesting, when I lived in Japan, no one knew anything about me. It’s not just my queerness or gender expression, but just like, interactions, or the use of language and how that really is different in all these contexts. In French too, like, everything is gendered. I see French like a big brick house. And I can’t really change the bricks in the house, and I can’t really put another brick in the house. So, it’s like… how can I actually put myself in this brick house when I use French? There’s so many different ways of expressing, and not expressing with these languages.

Yeah, this is the next character. The next one is my name.

So, it’s Le, or 乐. 快乐 is happiness and 音乐 is music. In the olden days, this top is kind of like for anything that’s medicine, or grass or nature. And so, this character itself represents what they consider as medicine, which is joy. Laughter is a medicine. It’s believed that joy in music has the power to heal ourselves. And I think this represents my name very clearly.

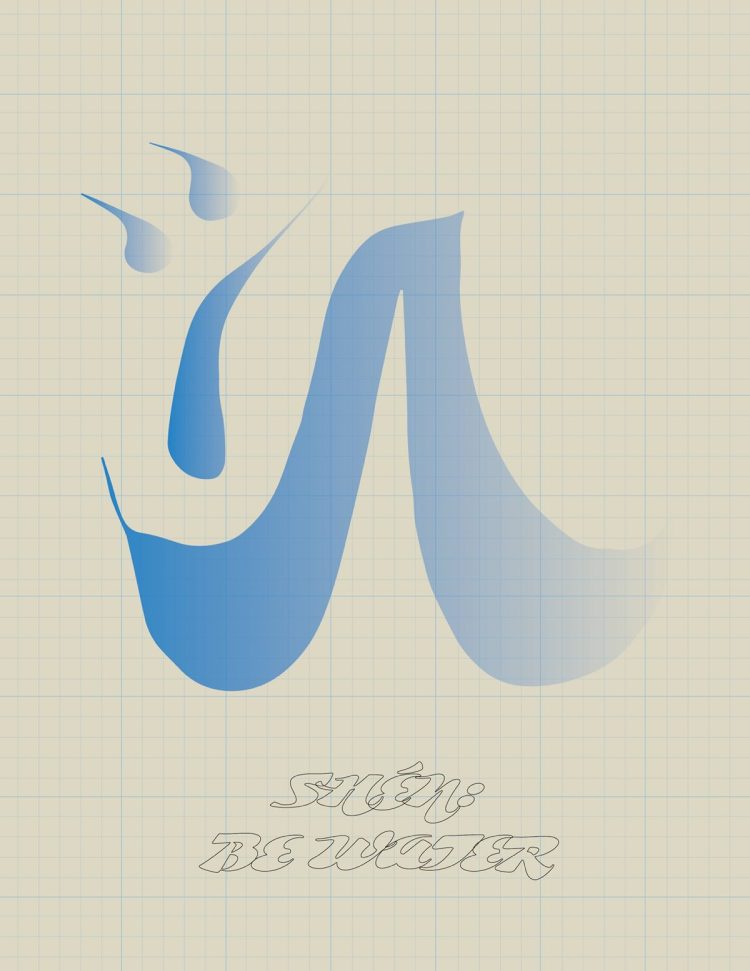

And the last one is the human radical 人 and three drops of water 氵. But it could be anything. It could be a river and rocks. You could interpret it how you want. And I intentionally made it so it looks kind of abstract. It’s the fluidity of humans, it’s the passage of time. It’s the souls that fly in the clouds. It’s the wild rivers that cut in the riverbeds, and it widens the riverbed through the passage of time. So, this is fluidity.

Yeah, those are characters I created. I guess I do want to go into why I chose these characters specifically. And part of it is just being part Chinese but not fully Chinese. Like, I grew up here for twenty years. And I don’t think I can ever live and feel at home in China. (Uh, especially, probably I would be imprisoned or something because of censorship.) I think navigating myself as a Chinese diaspora, it’s hard to connect with the language in a way that I can fully integrate it into my life. And I didn’t want to create a typeface that’s just ABC. Because I think there’s enough people creating ABC language. And I think for everyone, it doesn’t necessarily matter how fluent you are in your native language or how fluent you are generally to connect with a language. I think the intention is how do I have space in that language? Or will there be acceptance for me in that language?

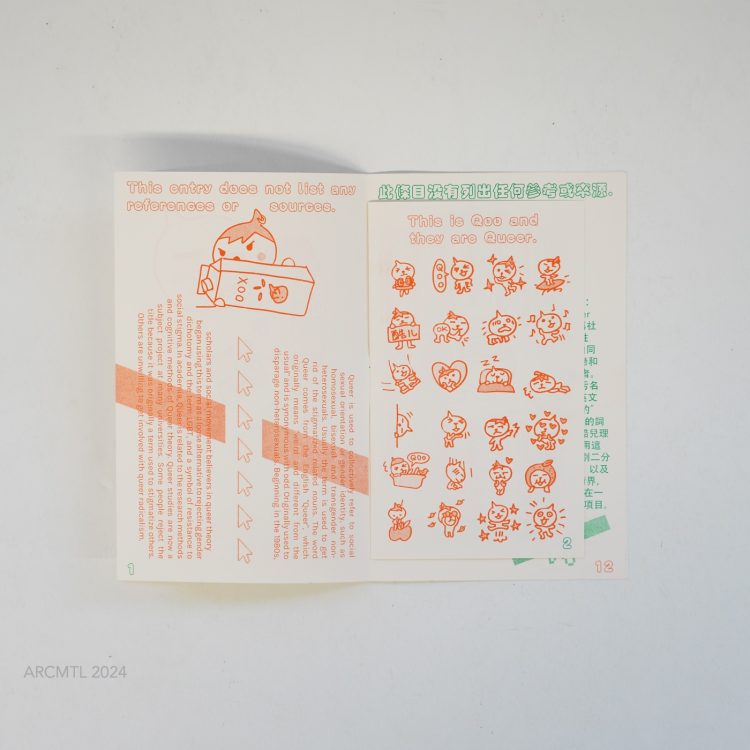

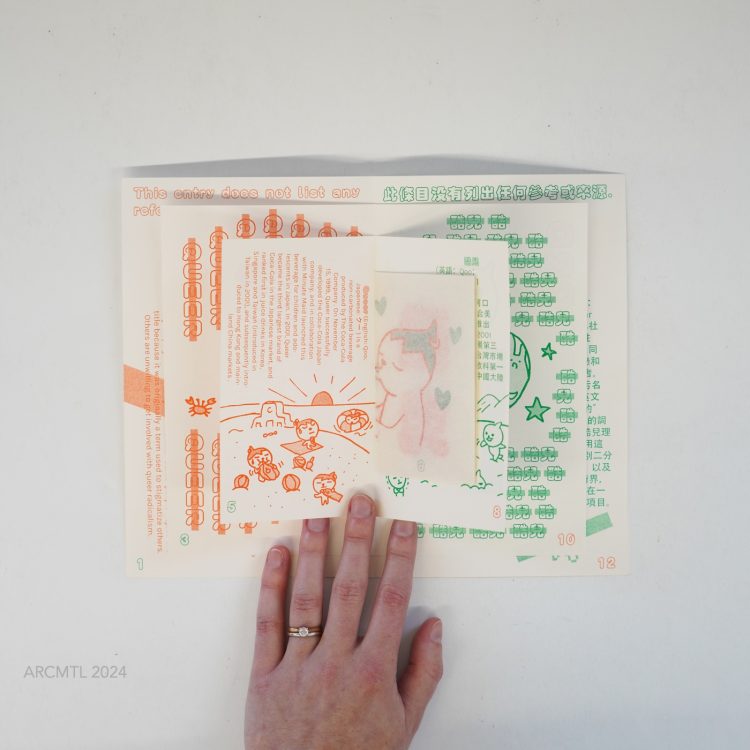

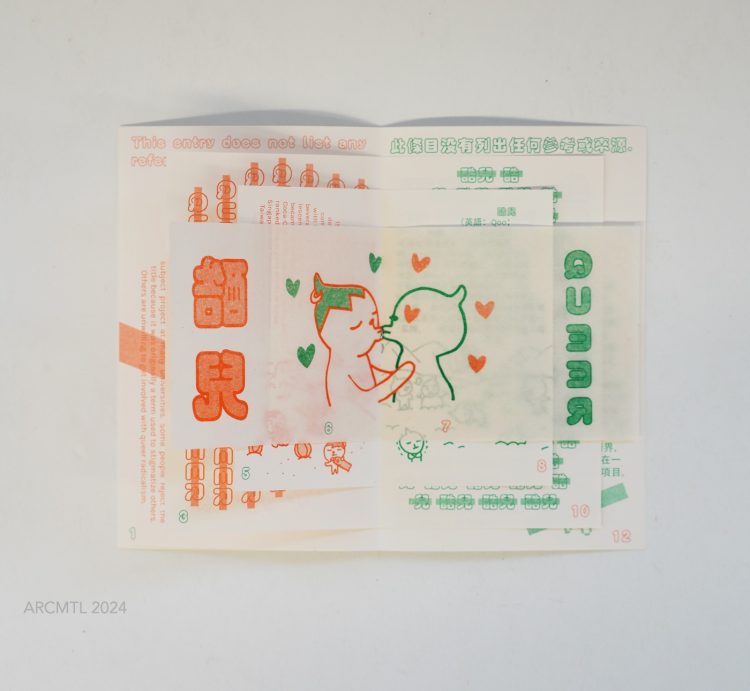

Another thing I wanted to talk about is translation. For example, this book that I made a long time ago. It’s with Chinese and English. And the context of this book was basically like, this character 酷儿 is used to censor queer content in China. It’s a just a little juice. Haha.

And basically, with this book, I wanted to do the opposite, where I used the characters’ history, but I censored the character. So, it’s like, oh, 酷儿 lives in a forest. It’s super happy. It’s dancing and playing in the park. But instead, I’m censoring the character. I think this project had a lot of things that came out of it. The existence of this project was actually banned in Shanghai, and I created a Japanese version of it in Japan. It’s travelled many places and has had a life of its own. And I think the biggest part of it was the context, but it was also the language as well. And I think like for all of us, if you make art that travels, it will exist in a new form everywhere it takes a new life in.

And what I wanted to say was self-translation is different than translation, right? Because translation, there’s always a binary. It’s always from source to target. If I’m translating Chinese, I will translate it in the Chinese that I think is correct.

But [in] self-translation, there’s no boundary. I can translate myself in a completely different voice than my English voice. And I can translate my Japanese voice in a completely different voice. So, there’s something about this book that also connects with how self-translation is inherently trans.

Yeah and I think there’s also, like, queering rules or dismantling structures. For example, typefaces, paper, reading things from left to right. How the page gets filled with text that goes this way, or the paragraphs get broken this way. You can dismantle those to reinvent – or not reinvent, but like, to ‘queer it’ is to take it apart and to make new. But ‘trans-ing’ is different. Trans-ing is, there is no binary thinking, I guess. So, I think a lot that came out of this was me thinking about how self-translation is trans. Yeah. And I guess it also ties in with the typeface project.

That being said, I have a few questions again. On the back of the cards, there’s a space for you to create your own character. I invite you to think of something in your own language. And I suggest you to think about: how do you envision yourself taking up space in that language?

And, it’s not just ABC, right? Like, you can do anything you want. How do you insert yourself in language? And how do you visualize yourself in a character? And as well, like, I think language also is dialectical. So the things we’re using today or the things we’re saying today, will that be captured or how will that be looked at in the future?

So, I’m creating this for myself right now. I’m not creating this for myself in the past. Like, queer slang. How does queer slang develop or become historical? In the future, what will people think of “slay,” “werk”?

Audience: [Laughs]

Le Lin: Will that be historical, or will that be part of the dictionary?

Yeah, so that’s what this project invites you to think about.